MAI 2018

NAMIBIA

-

Language: English (official); also spoken: Afrikaans, German, Oshiwambo, and other indigenous languages

Currency: Namibian Dollar (NAD)

Capital city: Windhoek

Population: ~2.5 million

Driving Side: Left

Best Time to Visit: May–September (dry season and best for wildlife viewing)

Weather: Hot & dry; cooler in winter

Power Outlets: Type D & M (220V)

-

💍 Honeymoon

✅ 17 day trip

✈ Berlin → AMS → LAD → LAD

-

🌌 Milky Way on Night 1 — pure magic above the desert

🏜️ Climbing Big Daddy & exploring Deadvlei

🦭 Kayaking with playful seals in Walvis Bay

🦏 Rhino tracking at Grootberg for our anniversary

🛖 Cultural exchange with Himba villagers

🦁 Wildlife safari at Etosha National Park — zebras, lions, elephants & more!

Contrasting landscapes, intriguing new cultures, exotic wildlife and an enchanting night sky, Namibia captured our hearts from the very first night we witnessed its magic.

Honeymoon mode on. First time in Africa

Itinerary

Day 1: Landed in Windhoek & hit the road FAST

Day 2-3: Tropic of Capricorn & Namib-Naukluft Park

Day 4: Sesriem Canyon

Day 5-6: Swakopmund

Day 7: Spitzkoppe & Twyfelfontein

Day 8-9: Rhino tracking at Grootberg Lodge and chill

Day 10: Himba Village Visit

Day 11-14: Safari at Etosha National Park

Dayy 15: Waterberg

Day 16-17: Quick peek into Windhoek’s city life

Day 1: Arrival & on the road

We landed in Windhoek and went straight for our 4x4 pick-up truck with a rooftop tent. After a quick supermarket stop, we hit the road toward Namib-Naukluft Park.

We had a lodge booked, but distances in Namibia are deceiving. As night fell, we stopped at a nearby lodge and asked if they had space. They did. We were the only guests. After dinner, we stepped outside and were stunned by the night sky. The Milky Way stretched across the horizon in perfect clarity.

Namibia is one of the darkest places on Earth. With zero light pollution, the stars feel close enough to touch.

Fun fact: The three best places to see the Milky Way are Namibia, the Atacama Desert in Chile, and Aoraki Mackenzie in New Zealand.

Days 2–3: Tropic of Capricorn & Namib-Naukluft Park

We left early and headed south, pulling over at the Tropic of Capricorn sign for the obligatory roadside proof before committing fully to the desert. From there, the scenic C19 carried us toward Sossusvlei via the Spreetshoogte Pass. The road climbs steeply with the car and then drops suddenly into the desert, revealing one of the widest views over the Namib plains. From there, the landscape flattened and quieted as we drove deeper into Namib-Naukluft Park, eventually reaching our campsite inside the park.

Camping at Sesriem Campsite meant sunrise and sunset without crowds, since staying inside the national park allows visitors to enter one hour earlier and stay one hour longer than everyone else. Sunset at Dune 45 was barefoot and still, the sand cooling as the light faded. At dawn, we climbed Big Daddy barefoot, a slow and humbling negotiation with gravity, before looking down onto Deadvlei. Once a clay pan fed by a river, it dried up when surrounding dunes cut off the water supply. The camel thorn trees died standing, preserved for centuries by the dry desert air and unable to rot. White clay, black trees, red dunes, and complete silence. It felt surreal.

Later, we stopped at the fairy circles, perfect round patches where nothing grows. Science talks about termites or plants fighting for water. Local stories talk about dragons or footprints of the gods. After dark, the sky took over. With almost no light pollution, the Milky Way stretched sharply overhead, making the desert feel endless even after sunset.

🚗 TIP: Deflate your tires before hitting the sand at Sossusvlei or you’ll get stuck.

Day 4: Rock, Shade, and Baboons

After the dunes, we crossed to the other side of the park and ended the day at Sesriem Canyon, a narrow gorge carved by the Tsauchab River over millions of years. The openness of the desert collapsed into something tighter and more intimate. Rock walls rose in stacked layers, shadows replaced glare, and patches of vegetation appeared where none should exist.

As evening settled in, the campsite turned chaotic. Baboons moved through confidently and loudly, completely unfazed by our presence. This place exists because rare flash floods still rip through the canyon during heavy rains, cutting deeper into the rock each time. For most of the year it remains dry and accessible, which makes walking through it feel like stepping into a pause between two extremes. Desert and river. Stillness and force.

The next morning, we tackled the canyon hike, following the dry riverbed through twists, narrow passages, and sudden pockets of quiet.

Days 5–6: Swakopmund Adventures

The drive west marked a clear shift. Fog rolled in from the Atlantic, the air cooled, and suddenly the dry desert met the ocean. Arriving in Swakopmund felt disorienting in the best way, a coastal town sitting right at the edge of the Namib.

We explored the desert from every angle. A 4x4 ride took us to Sandwich Harbour, where dunes collapse straight into the Atlantic. Kayaking with seals was loud and chaotic, with animals surfacing next to our boats like they owned the place. A sunrise hot air balloon ride slowed everything down again, drifting silently above dunes and fog as the light came up.

Walking through town, the architecture feels strangely out of place. Steep roofs, timber detailing, symmetry, and ornamental facades designed for a climate and culture that are not this one. As an architect, it is visually fascinating and deeply uncomfortable at the same time. Much of Swakopmund was built during German colonial rule, during the genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples between 1904 and 1908, when tens of thousands were killed, driven into the desert, or died in concentration camps under German command. These camps, including one on Shark Island, are often cited as early precursors to those later used in Europe. The buildings remain polished and photogenic, while the violence that enabled them is easy to overlook if you are not paying attention.

For a pause, we ended up in an old school café where coffee came with a full ritual. Rum warmed and poured tableside, sugar melted in, cream layered on top. Less a drink, more a small performance. It felt refined and slightly out of time, another reminder of how visible German colonial culture still is in everyday rituals across Swakopmund.

Just outside Swakopmund lies the Moon Landscape, a stretch of eroded hills formed from 450 million year old rock laid down in the early Paleozoic era, long before dinosaurs existed. The Swakop River and persistent erosion stripped away softer layers, exposing the rolling ridges and folded rock visible today. These ancient formations are geologically significant for their exceptional preservation and clarity, with comparable exposures found only in parts of Australia and the American Southwest. What remains is one of the oldest continuously exposed landscapes on Earth.

Day 7: Spitzkoppe & Twyfelfontein

The road north pulled us back into silence. At Spitzkoppe, massive granite peaks rise abruptly out of the flat desert, often called the Matterhorn of Namibia not for their shape but for how suddenly they stand alone. The rock here is older than the Alps and the Himalayas, formed deep underground and later exposed as the surrounding land eroded away. Some peaks reach over 1,700 meters high. We stayed for just one night, long enough to light a fire, go for a short dusk hike between boulders, and watch the rocks shift from warm orange to deep shadow. When night fell, the stars felt unusually close, framed by stone instead of open horizon. No spectacle, no storyline. Just rock, fire, and sky holding their ground.

Nearby, we made a side trip to Twyfelfontein, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most significant concentrations of rock engravings in southern Africa. More than 2,000 carvings date back between roughly 2,000 and 6,000 years ago and were created by early hunter-gatherer communities, ancestors of the San people. Animals dominate the imagery: giraffes, rhinos, and lions carved into sandstone, often near ancient water sources. Long before maps or borders, this landscape already functioned as a record, a meeting point, and a way of reading the land.

Days 8–9: Rhino Tracking at Grootberg Lodge & Chill

Anniversary timing felt right for something meaningful. At Grootberg, we tracked black rhinos on foot with local guides, moving slowly across the plateau, reading tracks, wind, and subtle signs in the landscape. These walks are not about thrill seeking. They exist because black rhinos are critically endangered, and active monitoring is essential for their survival. Tracking helps rangers protect individuals from poaching, understand their movement patterns, and keep populations viable in open conservancy land.

💡 Fun fact: Black rhinos are not actually black. The names black and white come from a linguistic mix up. “White” rhino comes from the Afrikaans word “wide”, referring to its wide mouth. Black rhinos have a hooked lip instead, adapted for feeding on bushes rather than grazing grass. They are more solitary and far more cautious by nature.

Staying at Grootberg Lodge completed the experience. It is a community run eco tourism project, with profits supporting conservation and local livelihoods. The lodge sits right on the edge of the plateau, opening onto vast mountain views. Quiet, intentional, and grounded.

Day 10: Himba Village

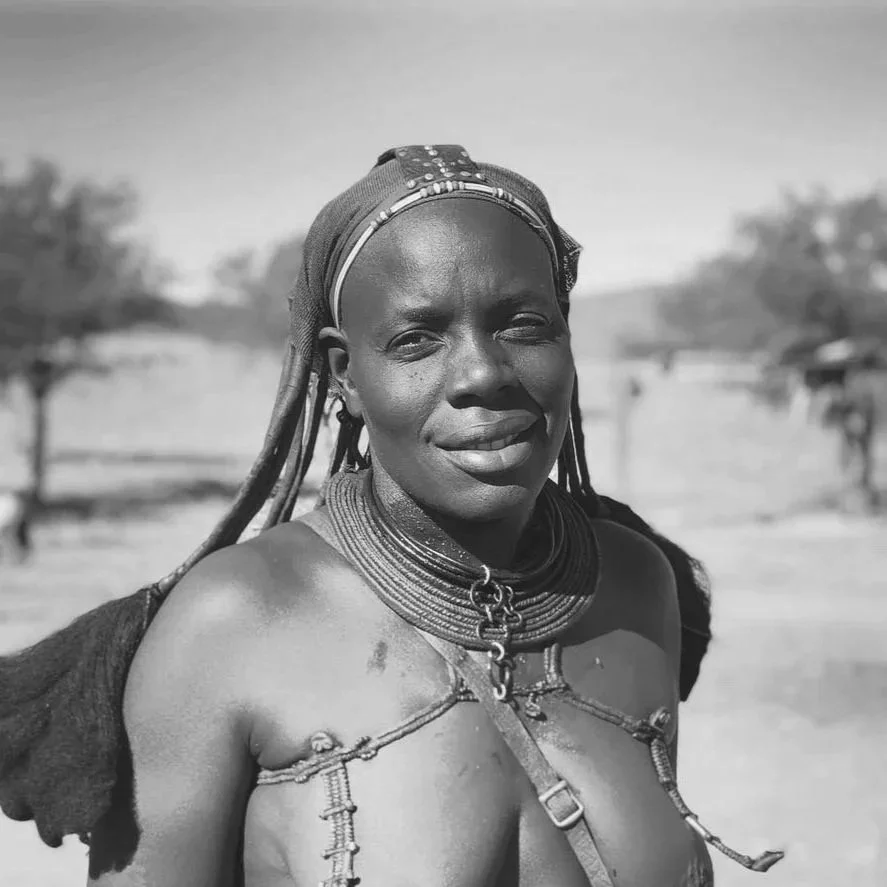

This was the most grounding day of the trip. Namibia is home to more than ten recognized Indigenous ethnic groups, including the San, Himba, Herero, Nama, Damara, as well as Ovambo groups, Kavango groups, and Caprivian groups. We chose to visit a Himba village because of their continued semi nomadic life in the northwest and because the visit could be arranged through a local contact rather than a staged tour.

Through a connection at Grootberg Conservancy, we met a local Herero teacher who spoke OtjiHimba, a variety of Herero, and translated for us during a visit to a Himba village in the Kaokoveld. The drive alone made it clear this was not a casual encounter. Rivers, rocks, sharp terrain, and long stretches without roads.

We sat together and talked about life, education, and death. Life is organised around cattle, ancestry, and continuity rather than accumulation. Death is understood as a transition rather than an ending, with ancestors remaining present through daily ritual. Formal schooling exists, but access is irregular due to distance and mobility, creating constant tension between traditional life and state systems.

Women cover their skin and hair with otjize, a mixture of butterfat and red ochre. It protects against sun and dryness and expresses identity and beauty. Because water is scarce, it is renewed rather than washed off. Men focus mainly on livestock and external relations, while women carry domestic work and cultural continuity.

The visit offered a rare insight into one of Namibia’s many Indigenous cultures. We left quietly, aware that listening mattered more than anything else.

🚫 FYI: You cross a veterinary line → no meat or dairy in the car, or it gets trashed.

Days 11–14: Etosha National Park Safari

Entering Etosha National Park through Galton Gate immediately shifted the pace. We started in the far west at Dolomite Camp, set high above the plains and noticeably quieter than the central camps. From there, we crossed east through the heart of the park, stayed at Okaukuejo Camp and Halali Camp, went slightly north, then looped back south and exited through Anderson Gate. Driving lodge to lodge made the scale tangible. Etosha’s vast white pan is so large it can be identified on satellite imagery, a reminder that this landscape is shaped as much by absence as by life.

In May, the dry season concentrates animals around water, turning each waterhole into its own quiet spectacle. Elephants bathed and splashed themselves, giraffes drifted past, zebras formed tight graphic patterns, lions appeared when patience paid off, and meerkats popped up living their best hakuna matata life. Etosha is home to the Big Five, a term originally used for the animals considered most dangerous to hunt on foot: lion, leopard, elephant, rhinoceros, and buffalo. We were never chasing a checklist, but over these days we saw all of them, with only the leopard choosing to stay invisible.

Nights were for listening instead. Distant calls carried through the dark, falling asleep knowing the park never really goes quiet, under an astonishing Milky Way.

Days 16–17: Windhoek City Vibes

Our final stop brought us back to the capital city. In Windhoek, we wandered through central streets, stopped at craft markets, and took time to experience daily life beyond the road. It felt busier and more layered than anywhere else we had been, a sharp contrast after weeks of wide open landscapes.

We tried local food, sampled Namibian beer, and soaked up the atmosphere. Windhoek felt less relaxed than the places we had just come from, but still worth exploring as a way to close the loop. A city shaped by history, movement, and transition, and a fitting final frame for the journey.

Design Tales

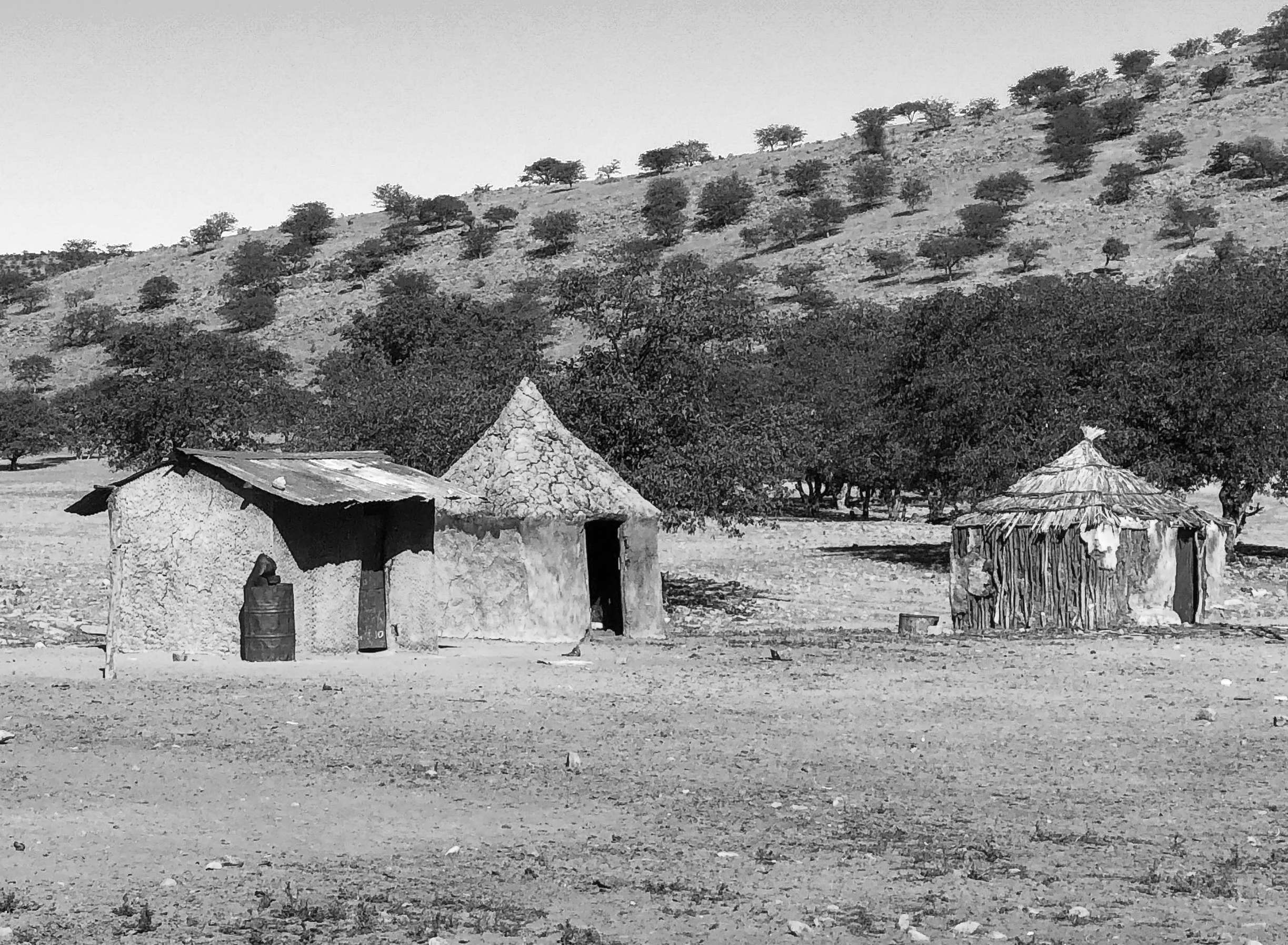

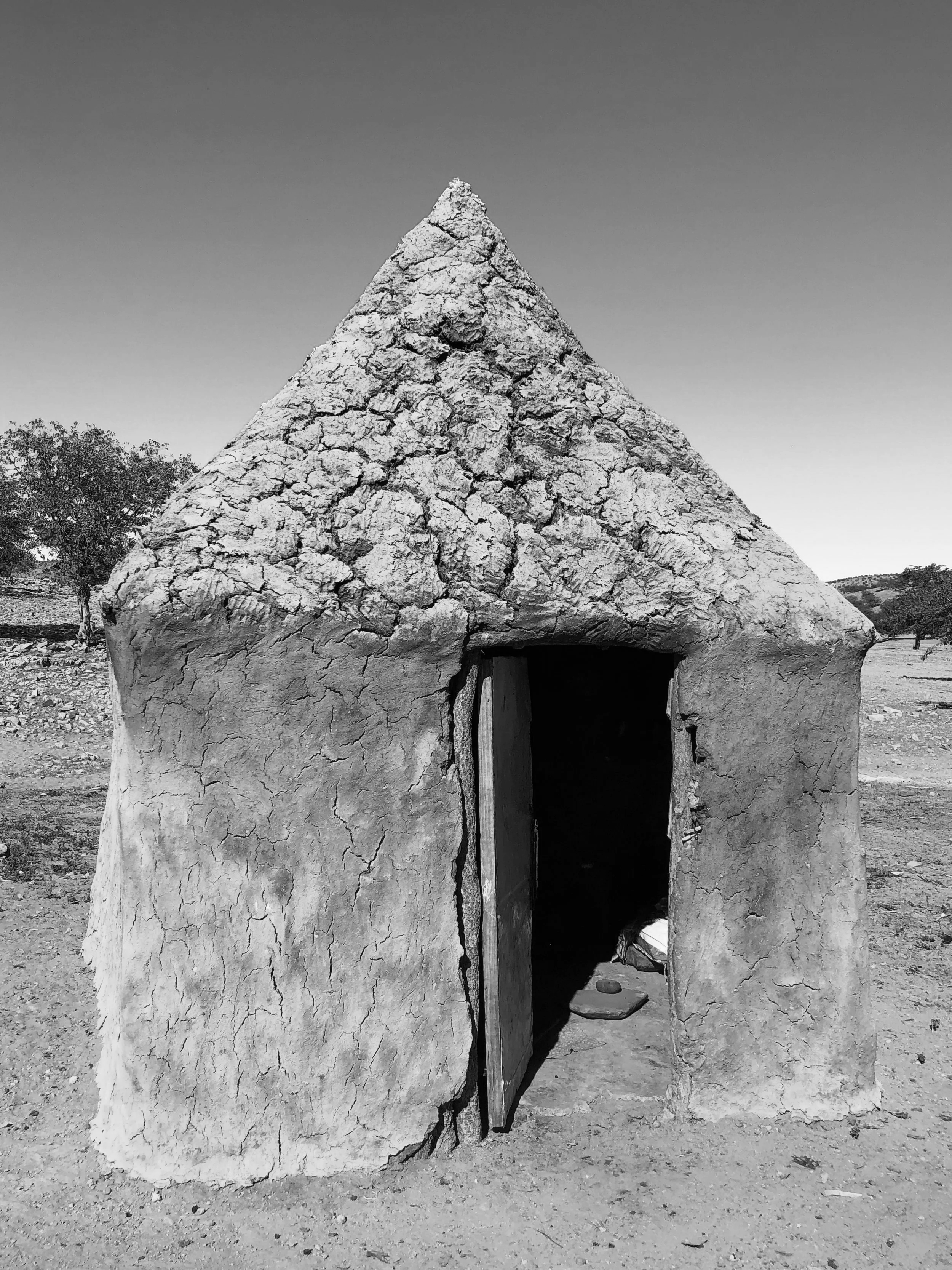

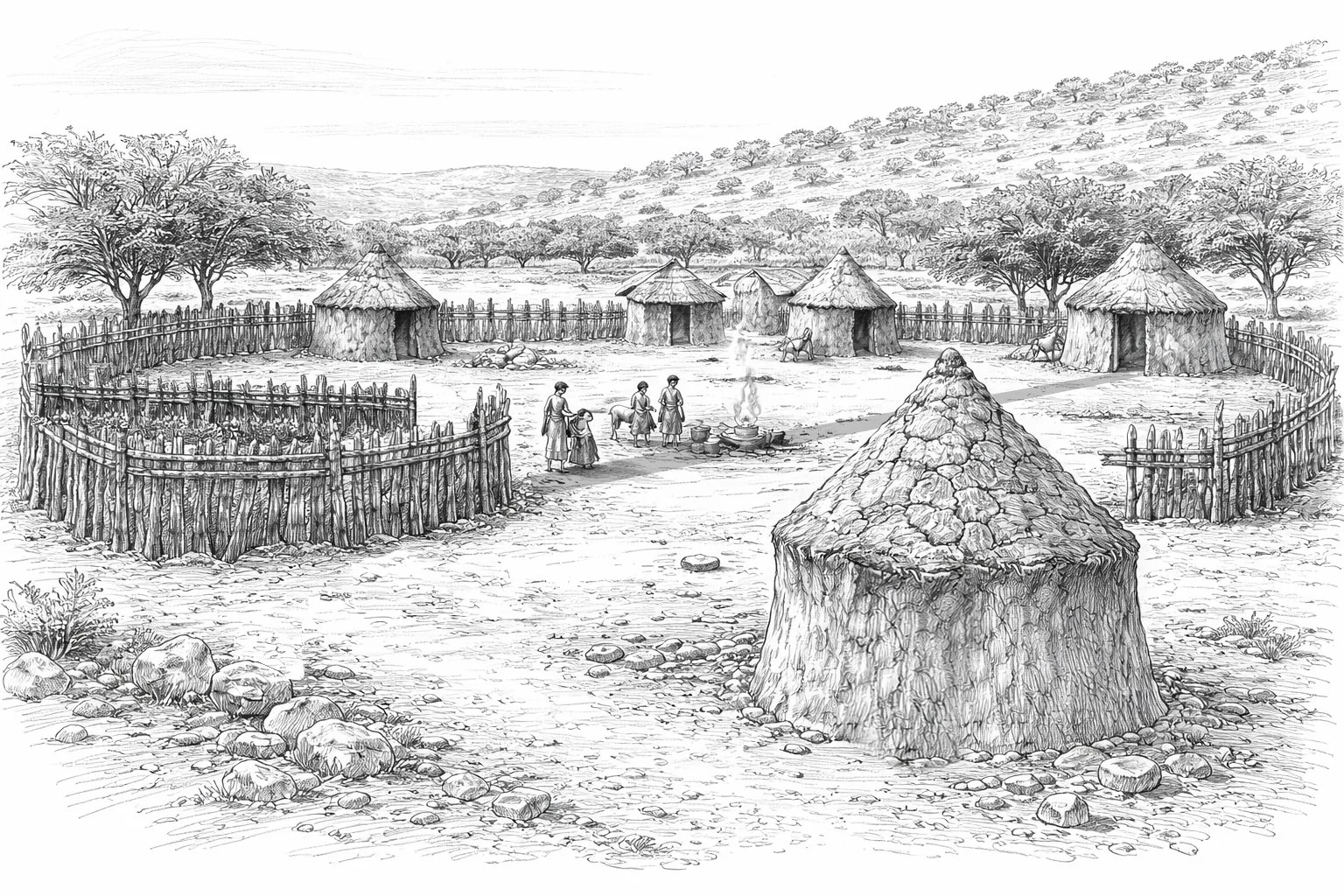

Vernacular architecture of semi-nomadic pastoralism

The Himba, estimated at between 20,000 and 50,000 people though no reliable census figures exist, practice semi-nomadic pastoralism across northwestern Namibia's Kunene Region. Their dwellings absorb a 40-degree daily temperature swing through material mass alone. Summer peaks above 45°C for over 300 days annually while winter nights approach freezing. Women build these structures from mopane poles, Colophospermum mopane, a termite-resistant hardwood, arranged conically at 3-4 meters height with vertical posts spaced irregularly at 30-40cm intervals. Walls are consolidated with adobe composite: red clay mixed with cattle dung, hand-plastered onto the frame. The surface shows erosive weathering, aggregate exposure, and irregular application, evidence of periodic reconstruction by successive generations who inherit this knowledge matrilineally from mother to daughter. Grass thatch forms the roof, often supplemented with black plastic sheeting where materials fail. The door opening measures 0.7m wide by 1.2-1.4m high, forcing occupants to stoop while blocking wind and dust. No windows. A central fireplace without chimney fills the interior with smoke that escapes through wall cracks and the doorway. During midday heat, this dark, smoke-filled space becomes refuge.

Spatial organization encodes hierarchy. In polygamous households where men average two wives, each wife occupies her own hut within the circular onganda or homestead. Huts position themselves around two elements: the okuruwo, the sacred ancestral fire, and the livestock kraal. The chief's hut aligns opposite the kraal entrance with the holy fire between them establishing an axis strangers cannot cross. Unmarried daughters and boys occupy separate structures with each location indicating kinship and status within the radial settlement pattern. Construction knowledge transmits matrilineally from mother to daughter, making women the technical specialists who possess and execute all building expertise even as patriarchal authority determines settlement location and mobility patterns. The architecture accepts impermanence. Structures are abandoned when grazing demands relocation, rebuilt at new sites with identical logic. This building system traces to at least the mid-16th century when Herero pastoralists migrated from Angola though construction methods likely predate this within older Bantu traditions. What appears as material decay is actually architecture calibrated to cyclical reconstruction rather than permanence, adapting to extreme climate through transmitted material knowledge in OtjiHimba, a Herero dialect spoken by this isolated population.

Editors Note

Namibia gave us everything: wild beauty, once in a lifetime experiences, and stories we’ll be telling forever. Here’s what stood out most for each of us:

🏆 Felix’s fave: Rhino tracking at Grootberg Lodge. Hiking through the wilderness to see rhinos up close was pure adrenaline and awe.

🏆 Sisi’s fave: The Himba village visit. Sitting in a mud hut, talking about life and death with the help of a local teacher. It was humbling, emotional, and unforgettable.

🚩 Tourist trap alert? The Etosha night safari in May. Cool in theory, but overpriced and barely any animals.

💡 Pro tip? Want to climb Big Daddy at sunrise or stay in the park for sunset? Book inside the park. It’s the only way to beat the gate times and the crowds.

Recs:

🥐 Food Spots

Solitaire Bakery, ICONIC. Tiny desert stop with Apple Pie that slap. A soft, almost absurd moment of comfort in the desert.

Swakopmund colonial café at Hansa Hotel. Old-school vibes, strong coffee, bomb cake 🍰

🛏️ Where to Crash (Lodges):

Grootberg Lodge. Insane views + rhino vibes

White Lady Lodge. Desert camping with rock-art energy

Dolomite Camp, inside Etosha = wildlife mornings 🦓

⛺ Where to Tent (Rooftop tent / camping vibes)

Sesriem Campsite. Inside the park = exclusive sunrise access ☀️

Spitzkoppe Campsites. Dramatic rock formations + unreal stargazing 🪨🌌